France in turmoil: ‘No one is willing to say the country needs to make sacrifices’

As Paris wrestles with political deadlock, questions are mounting over France’s ability to project strength abroad. RFI spoke to author and political strategist Gerald Olivier about the ongoing political crisis in France and its repercussions abroad.

France is once again mired in political turmoil after the National Assembly last week overwhelmingly rejected the revenue side of the 2026 budget.

Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu is trying a new method: rather than attempting to push a full budget through a fractured parliament, he aims to break spending into “absolute priorities” – security, energy, agriculture and state reform – and put each item to MPs separately.

The move is intended to avoid another budget showdown, after two years of governmental instability that have steadily chipped away at President Emmanuel Macron’s authority.

Critics, however, argue that the plan is merely a repackaged version of political improvisation – a delay tactic that risks further weakening France’s credibility at home and on the world stage.

Jean-François Husson, the Senate’s general rapporteur for the budget, delivered one of the sharpest criticisms of Lecornu’s move, describing it as a chaotic and ill-timed intervention.

“If you want to give the French a dizzying ride, you could hardly do it better than this,” he remarked, arguing that the government’s approach was generating more confusion than clarity.

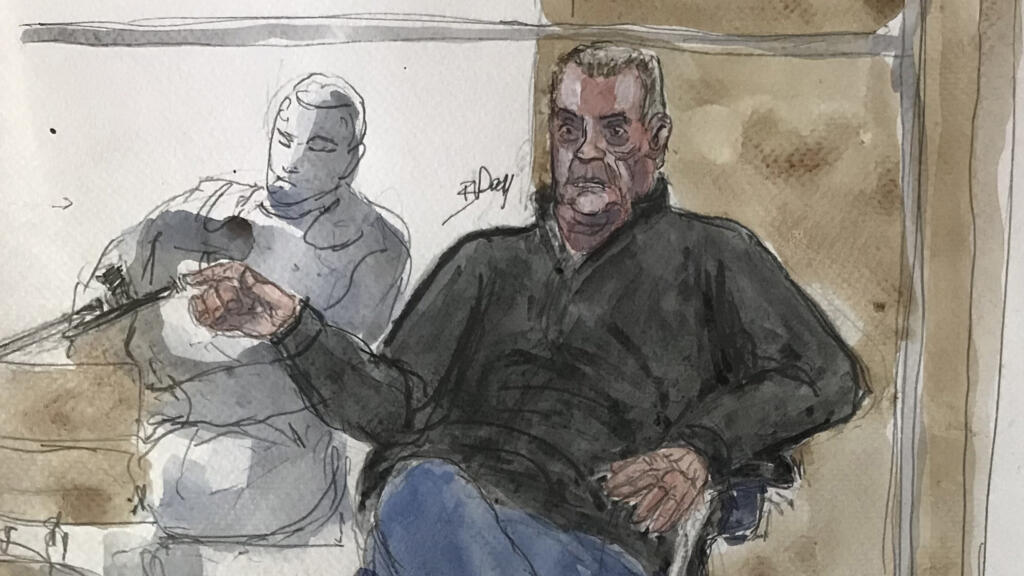

For author and political strategist Gerald Olivier, there is a deeper problem.

“France is sick, and France has been sick for a while,” he says. “We’re basically looking at a country with no government, no parliamentary majority and a total impossibility for any prime minister to put forward a credible programme.”

French lawmakers roundly reject income part of budget bill, send it to Senate

France technically needs to pass its budget by 31 December, but Olivier is quick to point out that this deadline has been missed before. “Last year, the budget wasn’t passed until February,” he notes.

If the same thing happens this time, the government can fall back on a temporary financial law that keeps spending aligned with the previous year’s budget for up to 70 days. A more drastic option – to rule by decree – exists as a constitutional backstop.

“This crisis exists because there is no majority in parliament,” Olivier says. “And it’s also because no party has had the courage to face the kind of medicine that France needs. That’s the larger issue.”

International credibility

As a major European power, France’s domestic politics do not stay domestic for long. International investors and European Union partners are watching closely, especially after recent warnings from credit-rating agencies about France’s deficit trajectory.

According to Olivier, the damage is already evident. “France is already in a recession, and there are investments simply passing the country by,” he argues. “No one knows what its tax status will be in the coming years.”

That uncertainty could have a ripple effect across the continent. France, he warns, risks becoming “economically weak and therefore politically weak within Europe”, potentially deepening divisions between EU member states.

France’s economy minister warns latest credit downgrade a ‘wake-up call’

“The one reassuring piece of news is that France is not the only one in this situation. Germany is in dire shape, Italy is shaky, Sweden is having problems. It seems today that everyone in Europe is the sick man of Europe,” he added.

Periods of political instability often attract external opportunists – whether governments, speculators or hostile influence campaigns. But Olivier remains cautious when asked whether foreign actors are already exploiting France’s woes.

“I don’t necessarily see it,” he says, “but if you want to consider fictional scenarios, you could find many.”

France’s EU membership, he argues, offers a buffer. “Having the EU behind you is reassuring. The idea of ‘Frexit’ would be disastrous. The euro provides protection.”

Still, the consequences of weakened governance can extend beyond the economy. A fragile budget could force France to scale back overseas military deployments – a shift that could alter power dynamics in parts of Africa and the Middle East. “This kind of instability is not healthy for anyone,” Olivier says.

A president without momentum

Macron’s political capital has been in decline since the 2022 legislative elections, when he lost his absolute majority. The surprise dissolution of the Assembly after the 2024 European elections only worsened matters, splitting the parliament into three mutually hostile blocs.

“It’s done tremendous damage to Macron,” Olivier says. “He was re-elected in 2022 because people didn’t want Marine Le Pen. He didn’t have the support he had in 2017, and disappointment set in.”

He argues that Macron himself triggered the crisis. “He dissolved the Assembly for no reason. The European elections had no influence on French politics, but he reacted as if they did – and he made things worse.”

Could the president break the deadlock? In theory, yes. “Macron could solve it instantly by resigning,” Olivier notes. “That would trigger a new presidential election, followed by fresh parliamentary elections. That’s how institutions are supposed to function.” But he sees no sign that Macron intends to take that step.

For now, he predicts “another 18 months of instability” with the possibility of yet another government reshuffle. “We’ve had four governments in 12 months. We could have a fifth one next year. There is no telling.”

France’s Le Pen asks Bardella to prepare for 2027 presidential bid

Eyes on 2027

With Macron unable to stand again, attention is already turning to the 2027 presidential race.

The National Rally – headed by Marine Le Pen and her rising protégé Jordan Bardella – enters the campaign in a strong position. Republican Bruno Retailleau could emerge from the right, France Unbowed’s Jean-Luc Mélenchon or Socialist Olivier Faure from the left. Names from the centre such as MEP Raphaël Glucksmann and the former prime minister from Macron’s Renaissance party, Manuel Valls, have been floated too.

Olivier’s concern is not who the candidates are but how honest they will be about the situation.

“No one is willing to say the country needs to make sacrifices,” he warns. “France is in debt up to 115 percent of GDP. Public spending is too high. But nobody wants to tell voters that the social state cannot remain as generous as it is.”

He singles out one controversial, far-right figure: “The only person honest about the economic reality is Éric Zemmour – and there is zero chance he will be the next president.”

Comments 0